This week we have Gertrude Stein’s short piece, “The Autobiography of Rose”, and whoever it was who chose to put it right after Trilling’s consideration of Hemingway, made a smart decision, for as Adam Gopnik succinctly wrote in a New Yorker article from (24 June, 2013),

“It isn’t the least of Stein’s virtues, or importance, that Hemingway was in many ways the popularizer of a style that she had invented. One could even say, to borrow Picasso’s famous disparaging remark about his imitators, that Stein did it first and Hemingway did it pretty. But, prettified or not, Hemingway’s style was the most influential in American prose for more than fifty years, and this makes Stein’s style less an outcropping than a bedrock of modern American writing.”

But as for me, alas, I don’t like Gertrude Stein, and I didn’t like her even more when I read the book about her relationship of accommodation with the Vichy government, as retold by Janet Malcolm in Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice…it is a good read, if you want to read about them instead of reading Stein herself.

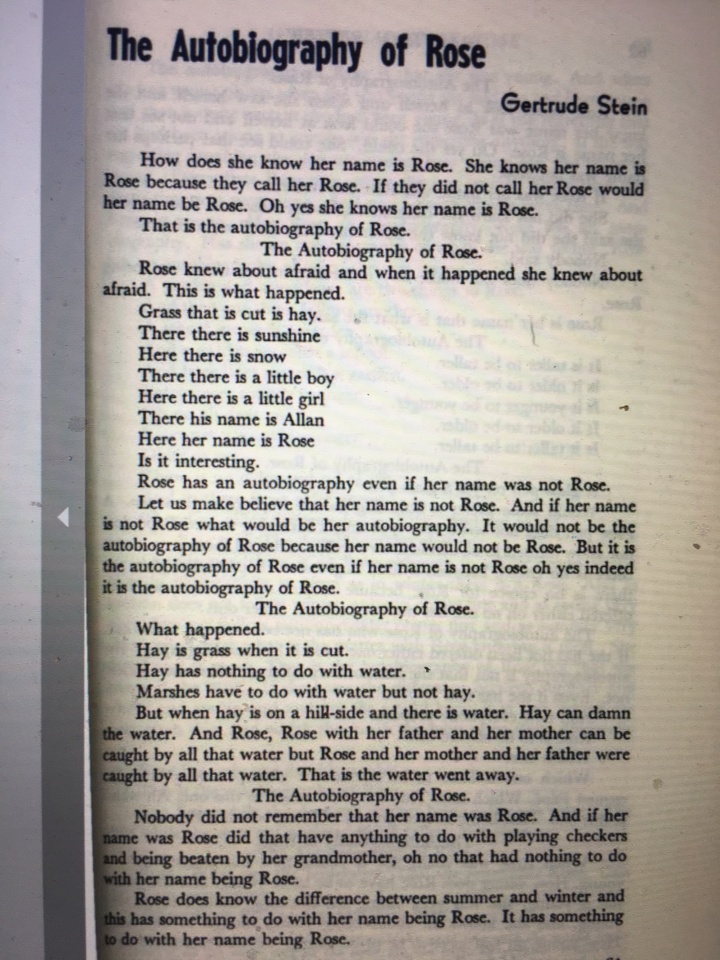

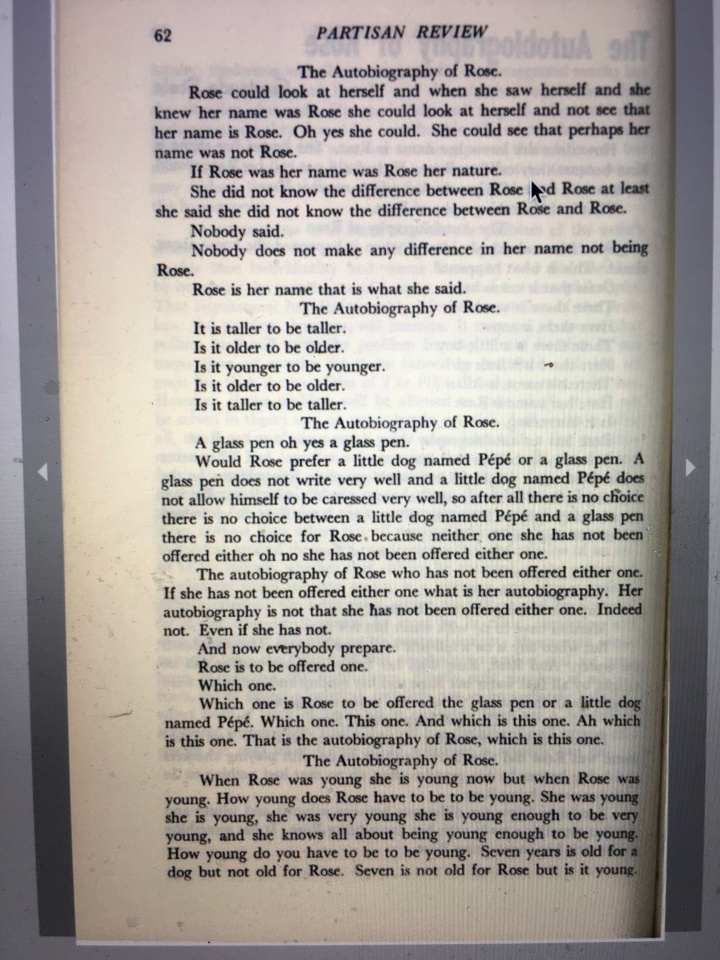

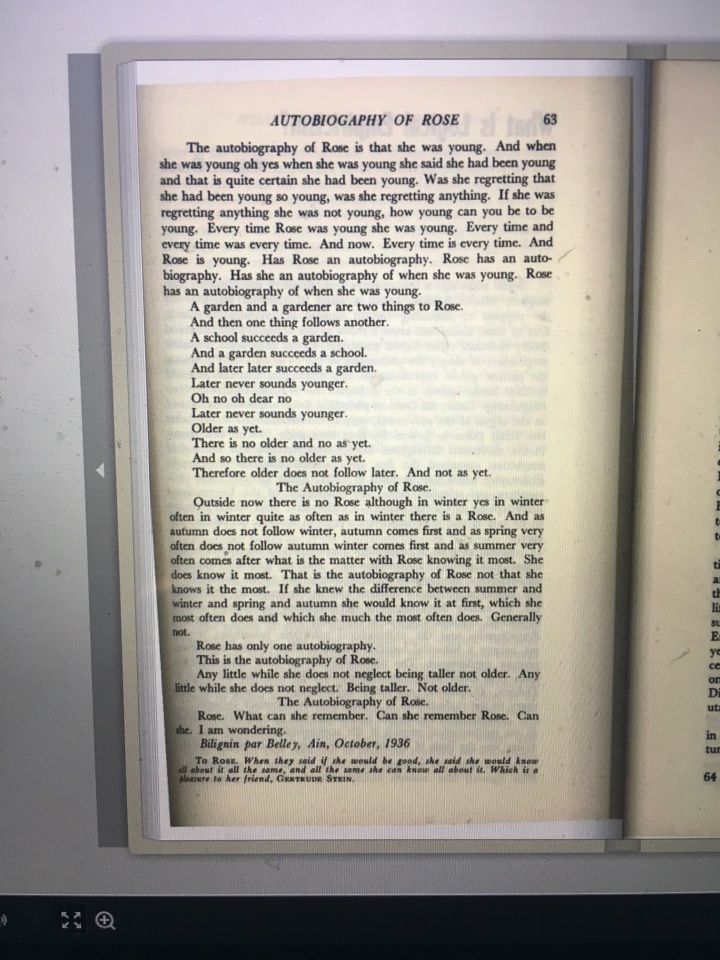

SO here is the text from Partisan Review: `You should be able to vary the size of the page on your computer..

SO…you can see how many of the marks of Modernism and post-modernism were invented here. Gopnik notices: “All marked styles—and any style that isn’t marked isn’t a style; what we call a “mannered” style is simply a marked style on a bad morning—hold their authors hostage just a bit. Stein’s style makes subtle thoughts sound flat and straightforward, and it also lets straightforward, flat thoughts sound subtle. Above all, its lack of the ordinary half-tints and protective shadings of adjectives and semicolons—the Jamesian fog of implication—lends itself to generalizations, sometimes profound, often idiosyncratic, always startling. It is the most deliberately naïve style in which any good writer has ever worked, and it is also the most “faux-naïf,” the most willed instance of simplicity rising from someone in no way simple.

What differentiates this kind of writing from someone like Hemingway, I would say, is that, whatever you think of Trilling’s critique of him, Stein’s repetitions and possible permutations through the power of absent punctuation sounds like the disease of intentional echolalia: to drain sentences of meaning altogether. In this way, its intention is the opposite of the estrangement/ Verfremdungseffekt. Instead of asking the audience to refuse to identify with the action of a play in order to make viewers process it intellectually, Stein’s style of writing evacuates its sentences of their referentiality in a world of concepts and idea and reduces it to the almost meaningless echolalia of children.

Gertrude Stein by Pablo Picasso

Gertrude Stein by Pablo Picasso

Next week: William Gruen begins to answer the question, “What is logical empiricism”?

I keep Gertrude Stein on my book shelf in the closet.As Sinutab , Draino, or Vix. As household necessity, it opens up the blocked mental territories from time to time. Ive no idea how it works tho.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha! AJ

LikeLike